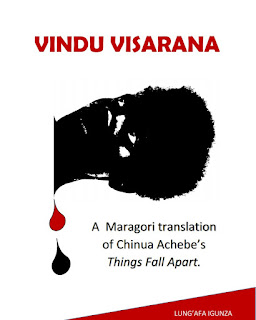

Translating Things Fall Apart to Maragori.

There are efforts to preserve Indigenous toungues through literature. Where original writing may be limited, translation can come in hand and rejuvenate interest. In such indirect documentation Indigenous Knowledge is able to be harnessed, preserved and applied in daily life and for future use. When a person strives to contextualize scenes through translation, there is more learning which by itself rewards such an initiative.

There is no documented orthography of Maragori language. Every writer happens to strike a relation with the Bible which is one early book in the tribe. But there were dynamics of the time. One was the use of letter 'l' in writing whereas it was 'r' or 'similar to 'r'' in pronunciation. There were instances where 'b' replaced 'v'.

Efforts to gather reasons as to why it was made so did not bear fruits with a general answer that that is what was taught at starter colonial schools.

Maragori has a phonetic similar to Kiswahili as many are other Bantu toungues. One good example is the 'cough' of verbs; kunyambua vitenzi. And this is where 'r' is justified as opposed to 'l'. 'l' is as a result of slang use that comes with shortening of subsequent 'r's'. An example is the word korera which for ease would be pronounced as kol'la bringing the second argument that there is no single 'l' but a double. Out of three replaced letters; '…rer…'

It would be difficult to cough the very verb, kora to assume other meanings had it been written as 'kola' which could already be meaning kol'la and lose the second meaning. Korera first means 'do for', secondly 'nursing a child' and third 'do at'. Writing kolela to mean 'nursing a child' would confuse a person if the very verb is coughed to doing it for another person. It would as prior written as kolelelwa. But it is pronounced as korel'lwa in slang (agreeable in direct speech) to avoid the successive 'r's'. The word is korererwa. Learners can be easily educated on the phenomena that 'r' is for writing and 'l'l' only applied in direct speech. If you join the first two 'r's', the meaning will come out clear as kol'lerwa; nurse for while the second korel'lwa; done for. There are many examples to give which can be followed up by the language ethusiasts in their reading where conflicts can be glaring if attemps to tame 'l' in place of 'r' is unchecked and without study, propelled.

The place of vowels is not in an effort to lengthen any of them between consonants. Listening to oneself when pronouncing the words, what would be thought to be a long vowel gains a medium range and in the spread of the sentence, the message is got. At the dictionary level the pronunciations can be denoted against the meanings but in writing the problem is not felt. There is special considerations for suffix 'aa' and in other scenarions 'ee'. In most cases they imply an active verb rather than accent. It does not apply to all and often when the verb is mid sentence. Where the verb is the last word in a sentence, it is common.

There were temptations to use vowels as prefixes to words. Iridiku, umurwaye, avasakuru, ovogeni are but a few examples. Normally that is what would appear in talks. But in writing they would rather be avoided because their presence is negligible. They do not also affect singularity or plural of words. For instance; iridiku – amadiku; ikivango –ivivango. But those that express singularity as indumba, inyingu, imburi and ekerenge are observed.

The sound mb is as a result of shortening 'muv'. Mbasu for muvasu, mbano for muvano, mbi for muvi, mbisi for muvisi. In writing the short form is avoided. It is equally applied to mutwi for mtwi, mukiri for mkiri, yaturiza for yatwiza among other examples.

This translation is therefore in desire to evoke an informed discussion on the need for a clear Maragori orthography that would quickly unlock the writing potential of the people who have interest in the language who may otherwise be prevented by the famous stereotype, 'the language is hard to read and write.' It is not.

......

NB. The italics for words not in English were lost during editting for the blog. You can find them in the book.

Comments

Post a Comment